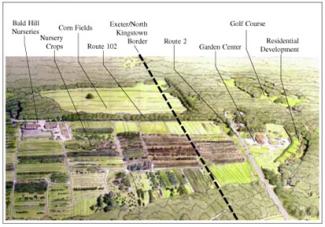

Agricultural District -- Existing Conditions Before Development

Agricultural District -- Introduction to the Site

The study area is on the border of Exeter and North Kingstown, at the intersection of Routes 2 and 102. Current zoning is primarily for house lots; 20,000 s.f. on the North Kingstown side; 3-4 acres in Exeter. A small amount of commercially-zoned land exists, most of it existing commercial properties near the intersection. The site is one of the main gateways to Exeter, with favorable access to the highway: thus some see it as a good development site. In North Kingstown, by contrast, the site is considered part of an agricultural greenbelt which should be protected from development. In any case, there is an obvious conflict between potential uses: good access and soil conditions make the site favorable for development; at the same time it is some of the last open agricultural land in the area.

Aerial view of Rt.102, with Bald Hill Nurseries in the foreground and in the distance the Rt.102/Rt.4 interchange in North Kingstown.

The view from Rt. 2 is an unusual one for South County, where so much of the roadside is lined with forest. Here you can really see the sky.

Most of the fields are used for an intensive mix of nursery crops and vegetables. Long, low greenhouses and chattering irrigation sprinklers add to the scene.

Agricultural District -- After Conventional Development

Agricultural District -- Conventional Development

Farmers planning to retire have few options here, since zoning allows only for residential development. With Half-acre lots on the North Kingstown side and 3 and 4 acre lots in Exeter, the farmland is quickly filled up with subdivisions. Usually the frontage lots get sold off first, lining once-scenic rural roads with houses. Large lot zoning, especially over 3 acres, can slow the subdivision process if values don't support the expense of road construction: but once lot prices reach a certain point, the road gets built and the farmland is lost forever. Faced with this situation, land-owners push for wholesale zoning changes, often to permit large-scale commercial development. This can be politically popular, as towns realize the fiscal impact of residential development on their tax base and look to commercial growth to support the cost of local schools and services. Continued farming is rarely part of the equation.

Large-lot development on farmland in New Jersey. Not only does large-lot suburban subdivision development ruin farmland, but it has nothing to do with the traditional pattern of communities like the old village center in the foreground.

Even with a peaked rook and gables, the building is set too far back on the lot to have much of a presence on the highway; mostly what you see is the parking lot.

In rural areas where commercial development is allowed, as in this development further South on Rt.2, the usual approach is to pave the front and put in a one-story building.

Agricultural District -- After Creative Development

Agricultural District -- Implementation Techniques and Examples

Like the other village plans presented in this manual, the plan for the agricultural district is based on concentrating growth into a mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly center. In this case however, specific measures are used so that the development of this site helps both to preserve agricultural land and to enhance the farm-based economy. The way it does this is by means of a Rural Village Development Ordinance (see Farming & Forestry Strategies report). The RVD would serve to implement a masterplan for development, similar to a Planned Development District, but including a mechanism to transfer growth away from farmland and into the village center -- in a way acting as a cluster ordinance for multiple parcels within the district. The positive impacts of using the clustering principle would be enhanced by allowing the conversion of the residential development rights now allowed by zoning to commercial development rights to be used in designated village growth areas. This would allow farmers to get a higher return for the sale of development rights on their land, allowing development of a relatively small part of the district to pay for the preservation of more farmland than could be saved based solely on the value of residential development rights.

Design standards for site planning, parking lots, architecture, streets, and other features would guide development. Limits on building size, in particular, would have to be carefully studied to prevent the construction of new buildings that are out of scale with the neighborhood. Local architecture could serve as the basis of the guidelines, using traditional barns and mill buildings as models for the size and proportions of structures to be allowed in the proposed development.

This village development approach would probably require shared water service and wastewater treatment. Again, this could be approached with the agricultural theme in mind; in many areas of the country treated wastewater is used to irrigate nursery crops -- recycling water pumped out of surface and groundwater supplies while providing a free source of nutrients.

A new commercial structure in South Deerfield, Mass. employs barn-like massing, wrap-around porches and traditional materials to help fit into an agricultural context.

Another building in South Deerfield was erected as the office of a post & beam construction company, using native timber and traditional construction techniques. As a result it feels very much like it belongs there.

Existing businesses like Schartner Farms, above, that are already succeeding in keeping the land in agriculture have to be part of the solution for the whole district.

Exeter has a long tradition of handsome agricultural and mill buildings. These can serve as sources for architectural and site planning standards appropriate to the area.